"And so, my friend, the...Revolution has begun: I send you my sincere congratulations. People have died — but don't let that trouble you — only blood can change the color of history."

— Maxim Gorky, Letter to Ekaterina [1905]

______________________________________

"All reactionaries must die," said the executioner as he lowered his saber, signaling the firing squad to empty their lead into the bodies of dozen-or-so men and women arrayed against the wall. They collapsed onto the ground, crumpled up and lifeless, and the next batch was brought out and executed, and then the next. Hundreds would die against that same wall this day, thousands over the week, millions across the country. And all in the name of the revolution.

How had Safehaven gotten here?

ISHME-DAGAN, OCTOBER 2017 M.C.

N.B. 13–14 years prior to the Fourth Krasnovan War.

I

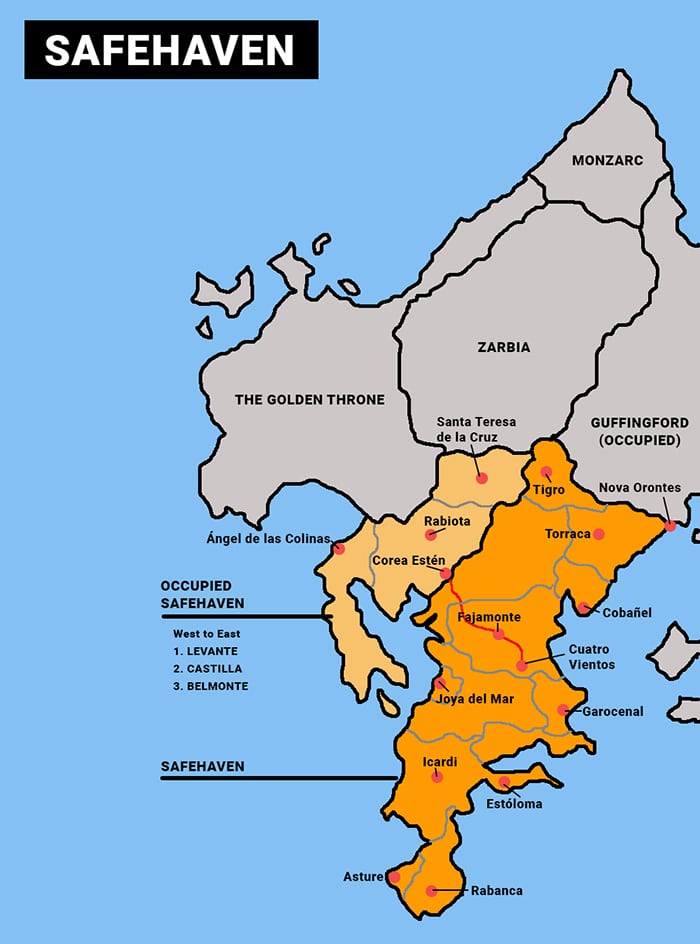

The town that would give the battle its name lay in ruins. Truth be told, Ishme-Dagan — which would now forever be in the history books — was only a minuscule part of the whole battlefield, which stretched for hundreds of kilometers in all directions. They would call it one of the largest tank battles in history, if not the largest. Over 110,000 tanks had fought on these hallowed grounds, and with them just as many other armored fighting vehicles or more. Now their burned-out, steel carcasses littered the charred grassland of northern Safehaven. By them, and in multifold quantities, lay the rotting corpses of millions of soldiers. Not even the thick, billowing smoke rising from the twisted remains of destroyed machinery could obscure the disfigured bodies of the dead. And amidst it, advanced triumphantly the victorious armies of the Golden Throne.

Emilio Talavera crawled hid among the dead as an imperial armored column rolled by him, not paying much attention to the carnage and instead focused on making good their victory by maintaining pressure against the collapsed Havenic armed forces which were by now in full rout. As soon as they disappeared, he threw off him the putrid remnants of a felled-man's torso. He himself was bleeding from a bullet wound in his gut, but he paid that no mind.

Crawling through the blood-soaked field, his body quivered from head to toe as he dragged himself with one arm. The other was on his wound.

In the distance, Emilio could still hear gunfire as small battles raged on. Pockets of surviving resistance, perhaps. Fighter aircraft roared overhead. He didn't have the energy to look up at them. Bombs exploded somewhere far away. But, he couldn't tell where exactly. His vision was fading and he was becoming rapidly weaker. Still, he persevered. He could not die here, not like this, now now. Back home, a newborn son waited for him. How many sons and daughters would grow up without a father after today? Not his, not if Emilio had anything to do with it. So he struggled on, pulling himself forward arm length by arm length, stopping only if an enemy patrol sounded as if it was passing nearby. There were enough bodies littering the ground for him to hide under no matter where he was. Then, as soon as they'd pass, he went on. He looked up to see the fiery remnants of Ishme-Dagan ahead, still far enough away to exasperate him. If he had an ounce of liquid in him, he might cry. Instead, he took a deep breath and trialed on until he reached the outskirts of the smoldering, utterly wrecked town.

To call it a town was perhaps an exaggeration. With little more than a few thousand inhabitants before the battle, it was truly little more than a village. Most of those people had fled south ahead of the war. Not all of them. Those that didn't were probably dead by now, although the bodies that Emilio saw as he made his way down the street were all dressed in military uniform. It was now abandoned and so dead was it that the Macabéans did not bother to even patrol it.

Slowly, Emilio crawled through the rubble until he reached the toppled walls of a once-building he recognized. He had arrived at Ishme-Dagan weeks after the battle began, spent less than a week within it, and was then told to sally and counterattack against imperial armored forces approaching it from the north. That was a few days ago. The counterattack had been defeated, his unit annihilated, and the Macabéans had moved on. But, he knew this building because it had been the pharmacy that the army had coopted and turned into a temporary medical station. Under the concrete and bricks of the rubble lay those who had been wounded and brought here to die. There were no survivors, at least not anymore. Emilio was all alone.

Although bombs had caused the building's roof to collapse, most of the walls were still half-standing and, despite his condition, he maneuvered through the debris. Frantically searching through what remained of the rooms, he sought out whatever medicine was still laying around. He found some, read the label, but it was something he didn't understand. He threw it out. Still searching, after some time, he finally found something useful: pain killers. He took some. Finally, Emilio found some instruments and scissors, and so he sat with his back to one of the still-standing walls and began to pseudo-operate on himself. The bullet that had hit him had gone through the other side and, given that he was still with life, he assumed nothing vital had been struck. Not far from him, there were some embers of something that had burned during the night and he used it to heat up a blade, which he then proceeded to press against the side of his stomach. He did the same to the exit wound. Sowing both sides up as best as he could, he knocked back a few more painkillers, and before he knew it Emilio had passed out.

II

"You, come here," said someone in a foreign language.

"Please, sir, I am but a villager. My wife, my daughter, I lost them. I merely returned to find them," said another, in Havenic.

"Nobody is left here," said the first man. "Come here, now."

Emilio opened his eyes slowly. He felt tired, groggy, and his vision was at first quite blurry. He did not know what was going on outside, neither did he truly register it. That is, until the gunshot sounded and reverberated against the broken walls of the empty, hollow town of Ishme-Dagan. "Idiot," said the first man, still speaking a foreign tongue that Emilio did not understand. "Keep looking for other survivors. Don't spend too much time on each one. If they don't surrender, kill 'em."

There was the sound of a boot crunching rubble beneath its sole coming from inside the one-time pharmacy. Emilio tensed. He was toward the back of the building, but the pharmacy wasn't large. The sound of footsteps came closer. Whoever it was, the person was pushing aside debris, opened cabinets, tossed aside bodies, and did what sounded like a thorough investigation. From outside, "Find anything? Don't waste your time, do a quick search. We still have other buildings before we move on to the next village."

"Nothing yet," said another man, also in a foreign language. They were speaking Díenstadi. These were Macabéan soldiers.

"Hurry," replied the first. "It will be noon in two hours and I would like to eat on time today."

Inside, the footsteps came closer. Looking around him, Emilio found the blade he had used to cauterize his wound. He grabbed it with a clenched fist and slowly picked himself up off the ground, using the wall behind him as a crutch. Slowly, and quietly, moving to the forward edge of the room, he took up a position just behind the opening where there once stood a door. The Macabéan soldier stepped closer. Emilio cut his breathing. From the other side of the opening poked in the muzzle of a rifle. Then stepped a black boot. It seemed an eternity as the soldier stepped into where the Havenic fugitive was hiding. Before either of them truly knew what was happening, Emilio went to stab him in the neck. But just as cold, hard steel was about to make contact with warm, soft flesh, he heard a buzzing sound above him. Looking up, he saw, for a very brief moment, a low-flying drone. And that's about all he saw, as something struck him in the head and he, once again, went out cold.

By the time he woke up, he was no longer in Ishme-Dagan.

III

Emilio awoke inside a cold cell with concrete floors and non-insulated brick walls. The fourth wall was made of bars, with a locked door on one side. How did he get there? The last thing he remembered was waking up within the ruins of Ishme-Dagan.

As he slowly regained consciousness, he realized that he was in a cell with dozens of others. In fact, it was so overcrowded that, like him, most slept on the floor. Only a lucky two were on cots. Others noticed him awake, but said nothing. They seemed destitute, lacking of energy, and hopeless. Most wore the uniforms of Havenic soldiers, although many did not. On the other side of the cell door, across the hall, was another one just like his and it too was filled to the brim with Havenic prisoners.

"What is this?" he asked, to no one in particular.

One man, behind him, replied, "El infierno, hermano."

Emilio rubbed his head, which hurt quite a bit. Where his hand touched there was a large, hard bump and as his fingers traced the pain he felt a scar. That suddenly reminded him of the wound in his gut, and he frantically lifted his shirt to inspect it. It had been infected the last he remembered. How long had it been? How bad had the infection gotten? But when he looked at it, there was no more pus and, instead, there were professional stitches. Someone had cleaned him up.

A uniformed soldier appeared outside. He struck the bars with his baton loudly, and then his narrow eyes settled on Emilio. He said, in his alien, Díenstadi tongue, "You, you are awake." Seeing that the Havenic was inspecting his wound, the soldier chuckled and added, "You can thank the empire for that, friend. If it was up to me, though, the lot of you would have been shot where we found you."

"Mi familia," said Emilio, who didn't understand a word that the guard was saying.

"Familia?" repeated the guard, who obviously did not know the language of his prisoners. "What is that? Family? Oh, you'll be seeing them soon enough. For now, it's time to eat."

He unlocked the cell door and ordered the group inside to line up outside against the bars. When Emilio stepped out he noticed the armed soldiers standing above them, on passages protected by concrete barriers. They were all pointing their rifles at the prisoners. The guard opened the other door and had those do the same thing as their predecessors. He then walked down the hall and continued doing the same thing until what seemed like more than a hundred Havenics in rags and worn uniforms were standing in a line on either side. The guard inspected them all, lightly hitting some in the stomach or in the leg with his baton, as if to prove to them that in his power was the capacity to do much worse. Above, the other soldiers with rifles grimly kept their posture, never lifting or moving their rifles, not even to scratch an itch.

They were finally moved out of the hall into another one, which they followed until turning down a different path until, finally, they reached a large mess hall. There were thousands of prisoners already seated at metal tables in the large room. Emilio and his group were led past these tables to a long line, in which they waited until they reached the back where behind a glass barrier there was a kitchen and cooks. A single bowl of god knows what was passed to each one of them through an opening in the glass, which they took to a table that the guard led them to. With all the hub-bub it was quite loud, as the guards evidently did not care if the prisoners talked among themselves. But, at first, his table was silent. Everyone was too focused on eating. Emilio couldn't even remember when the last time he had a bite of food was. How long since he had been captured? His last meal was the day before that.

Finally, with some food in his stomach, he looked up at the man across from him and asked, "Are you all prisoners of war?"

The man nodded, and replied, "Most of us. Some are just villagers that were picked up after the battle. Who were you with?"

"2189th battalion, 219th infantry division," answered Emilio.

He heard a laugh from beside him, and another man said, "You poor assholes were part of the reinforcements that were supposed to turn the tide, weren't you? The ones that counterattacked. I heard they chewed you up and spat you back out, and that those who lived should consider themselves lucky. Not that any of us faired any better. My unit retreated south early on and those bastards still managed to catch up to us. Now I'm here."

Emilio shrugged. "I don't remember much, to be honest," he said. "I was shot early in the afternoon, not long after we counterattacked. Where are we? How far from the front?"

"The front?" barked the same man, "Hah! There is no front, compadre. Our boys are in headlong flight southward. I've heard rumors of a new line, but every new prisoner who walks into these walls tells me the same thing. Our army is no longer an army, just rabble in rout. Nos jodieron bien en Ishme-Dagan. The cream of the crop, and all the new armor we imported, is gone. Dead. Destroyed. No more. The war is as good as over."

"And us? What happens to us?" asked Emilio.

The man shrugged. "¿Quién sabe?"

As it turned out, all of these prisoners, including Emilio, would be on their way home. But only after almost a years' wait. Every day for the next nine months they did the same routine, spending almost all of their day in a cell, with about 30 minutes of exercise time split up into three blocks — morning, afternoon, evening — and two meals. The latter was always the same gruel they ate that day. The food never got better. And the worst was yet to come.

When winter came the bitter winds entered through the small holes in the walls to freeze the prison's inhabitants. Many saw their toes and fingers succumb to frostbite. A great deal died from the cold and illness. But the cells were always full, because there were always new prisoners of war to replace the dead. The prisoners buried their own and, ironically, belonging to a burial crew became a respite from the misery. Those chosen were bussed to a field less than five kilometers away from the prison, which Emilio learned had been co-opted as a prisoner of war camp, where they dumped the bodies into a communal pit and covered back up with dirt. It was gruesome work, but burial crews got a third meal and it gave them almost eight hours of time outside of their cells. It was, in their world, a great privilege. Emilio did what he could to always be chosen. Typically, that meant being a "good boy" and doing what the camp guards told him, including informing against prisoners who caused trouble. When one of the prisoners tried to stab him in the showers, the Macabéans moved him to a separate barracks building that was less crowded and housed the "privileged" prisoners of war — typically, the officers and other informants who had been "done."

Not all the officers were well-off. They were, by virtue of their position in the Havenic army, the best informed of all the prisoners in Macabéan hands. Many came back from interrogation scarred from torture. Some told Emilio their stories. They were asked questions like: How many divisions around this city? What was the status of the equipment of these units? Who were their officers? All questions with answers that most officers in here would not know because the situation had changed drastically since the end of the Battle of Ishme-Dagan. The Havenic army was in disarray, its leadership in chaos, and nobody knew much except what was immediately relevant to them. The prisoners in this camp knew even less, although the worst torture was reserved for the most recent newcomers.

He was spared much of the violence, largely because of his willingness to cooperate to the extreme and the fact that he had been a mere plebeian. But he saw the beatings in the courtyard on almost a daily basis. Prisoners who made it to burial duty and tried to escape in the field were simply shot. Those desperate enough to steal food in the mess hall were beaten to nearly an inch of their lives, and many were just killed afterward by the man they had tried to steal from.

By the war's end in the summer of 2018, Emilio did not consider himself lucky to be alive. His life had come at the cost of his humanity.

IV

By the time he was given his freedom, loaded onto a bus, and driven southward, Emilio had almost forgotten about his wife and newborn son.

He looked dejectedly out the window toward the countryside. The land he had been sent to defend was now under foreign occupation, ceded to the Golden Throne by treaty. In this new post-war world, there was no room for Havenics like him in their old land. Millions of his kind were loaded on busses like this one, or else trucks or made to move on foot, and deported to south of the new border between the empire and republic. They stopped twice a day for bathroom breaks but were fed on the move. The food was no longer that soup, which Emilio had become accustomed to. They were given military rations, which were not much better. Once on the other side of the frontier, they were dropped off with only the clothes on their back — some of them were "fortunate" to get new prisoner garb but many still wore the same uniform they had been captured in — and their transports turned around, never to be seen again. Now "home," the once prisoners were expected to make it on their own. Tens of thousands stood there, at first, motionless, and clueless about what to do next. There were no Havenic authorities there to help.

How far the war had come, whether the Golden Throne's armies had fought here, Emilio did not know. But, it all looked like a warzone to him. Not all of it could have been caused by the fighting, that much was clear. The border town he had been left at, Juradeño, was in a state of anarchy he would almost immediately find out. With no traces of the Havenic army, the hundreds of thousands of released prisoners organized authority of their own. It was a totalitarian authority. The townspeople were long gone, or dead. Some of their women had been left behind and now "worked" as prostitutes. To call it work was hyperbole because they were not paid. There was no food for anyone except that controlled by the town authority, which was little more than a group of strongmen. Emilio and those who had come with him were told to move along at the point of the gun.

He, at any rate, had only one thing on his mind: returning to his wife. Before the war, they had lived in the city of Cuatro Vientos and he assumed they were still there. And so, in that direction, he walked the long journey home.

Although the richest farmland had always been in the north, the lands now occupied by the Golden Throne, he expected some sign of life and abundance here. But the fields were barren and there were no workers tilling the soil. It looked as if there would be no harvest this year. Hunger did not have to wait for the harvest, or lack thereof, however. The side of the road was inhabited by the homeless refugees produced by the war. They begged for food and water from those who didn't have any either. Women sold their bodies to those who promised them scraps, only to find out that they had been taken advantage of half of the time The corpses of those who did not make it were left strewn where they had fallen, sometimes in the middle of the road itself. Emilio, and others, lived off the weeds. The water he drank he produced overnight, using the skills he had learned in the army to collect it from the condensation, using his clothes to funnel it into a canteen he had found on a dead man's body. Somehow, he survived. But, truth be told, it hardly felt like survival. He felt dead in a dead land.

He should have hated the Macabéans. He should have hated the government that got them into this war, in the first place. Instead, he hated the people. He hated how they robbed from each other. He hated how they took advantage of each other. He hated how they gave up and died. He hated their ignorance and their plight. He hated how they could not take care of themselves, even though it wasn't all their fault. He hated that they could not pick up the pieces and had instead devolved into barbarians.

This hate would grow into much, much more when he arrived home.

It defined his new self, his ambitions, and his objectives.

It would come to define Safehaven.

— Maxim Gorky, Letter to Ekaterina [1905]

______________________________________

"All reactionaries must die," said the executioner as he lowered his saber, signaling the firing squad to empty their lead into the bodies of dozen-or-so men and women arrayed against the wall. They collapsed onto the ground, crumpled up and lifeless, and the next batch was brought out and executed, and then the next. Hundreds would die against that same wall this day, thousands over the week, millions across the country. And all in the name of the revolution.

How had Safehaven gotten here?

ISHME-DAGAN, OCTOBER 2017 M.C.

N.B. 13–14 years prior to the Fourth Krasnovan War.

I

The town that would give the battle its name lay in ruins. Truth be told, Ishme-Dagan — which would now forever be in the history books — was only a minuscule part of the whole battlefield, which stretched for hundreds of kilometers in all directions. They would call it one of the largest tank battles in history, if not the largest. Over 110,000 tanks had fought on these hallowed grounds, and with them just as many other armored fighting vehicles or more. Now their burned-out, steel carcasses littered the charred grassland of northern Safehaven. By them, and in multifold quantities, lay the rotting corpses of millions of soldiers. Not even the thick, billowing smoke rising from the twisted remains of destroyed machinery could obscure the disfigured bodies of the dead. And amidst it, advanced triumphantly the victorious armies of the Golden Throne.

Emilio Talavera crawled hid among the dead as an imperial armored column rolled by him, not paying much attention to the carnage and instead focused on making good their victory by maintaining pressure against the collapsed Havenic armed forces which were by now in full rout. As soon as they disappeared, he threw off him the putrid remnants of a felled-man's torso. He himself was bleeding from a bullet wound in his gut, but he paid that no mind.

Crawling through the blood-soaked field, his body quivered from head to toe as he dragged himself with one arm. The other was on his wound.

In the distance, Emilio could still hear gunfire as small battles raged on. Pockets of surviving resistance, perhaps. Fighter aircraft roared overhead. He didn't have the energy to look up at them. Bombs exploded somewhere far away. But, he couldn't tell where exactly. His vision was fading and he was becoming rapidly weaker. Still, he persevered. He could not die here, not like this, now now. Back home, a newborn son waited for him. How many sons and daughters would grow up without a father after today? Not his, not if Emilio had anything to do with it. So he struggled on, pulling himself forward arm length by arm length, stopping only if an enemy patrol sounded as if it was passing nearby. There were enough bodies littering the ground for him to hide under no matter where he was. Then, as soon as they'd pass, he went on. He looked up to see the fiery remnants of Ishme-Dagan ahead, still far enough away to exasperate him. If he had an ounce of liquid in him, he might cry. Instead, he took a deep breath and trialed on until he reached the outskirts of the smoldering, utterly wrecked town.

To call it a town was perhaps an exaggeration. With little more than a few thousand inhabitants before the battle, it was truly little more than a village. Most of those people had fled south ahead of the war. Not all of them. Those that didn't were probably dead by now, although the bodies that Emilio saw as he made his way down the street were all dressed in military uniform. It was now abandoned and so dead was it that the Macabéans did not bother to even patrol it.

Slowly, Emilio crawled through the rubble until he reached the toppled walls of a once-building he recognized. He had arrived at Ishme-Dagan weeks after the battle began, spent less than a week within it, and was then told to sally and counterattack against imperial armored forces approaching it from the north. That was a few days ago. The counterattack had been defeated, his unit annihilated, and the Macabéans had moved on. But, he knew this building because it had been the pharmacy that the army had coopted and turned into a temporary medical station. Under the concrete and bricks of the rubble lay those who had been wounded and brought here to die. There were no survivors, at least not anymore. Emilio was all alone.

Although bombs had caused the building's roof to collapse, most of the walls were still half-standing and, despite his condition, he maneuvered through the debris. Frantically searching through what remained of the rooms, he sought out whatever medicine was still laying around. He found some, read the label, but it was something he didn't understand. He threw it out. Still searching, after some time, he finally found something useful: pain killers. He took some. Finally, Emilio found some instruments and scissors, and so he sat with his back to one of the still-standing walls and began to pseudo-operate on himself. The bullet that had hit him had gone through the other side and, given that he was still with life, he assumed nothing vital had been struck. Not far from him, there were some embers of something that had burned during the night and he used it to heat up a blade, which he then proceeded to press against the side of his stomach. He did the same to the exit wound. Sowing both sides up as best as he could, he knocked back a few more painkillers, and before he knew it Emilio had passed out.

II

"You, come here," said someone in a foreign language.

"Please, sir, I am but a villager. My wife, my daughter, I lost them. I merely returned to find them," said another, in Havenic.

"Nobody is left here," said the first man. "Come here, now."

Emilio opened his eyes slowly. He felt tired, groggy, and his vision was at first quite blurry. He did not know what was going on outside, neither did he truly register it. That is, until the gunshot sounded and reverberated against the broken walls of the empty, hollow town of Ishme-Dagan. "Idiot," said the first man, still speaking a foreign tongue that Emilio did not understand. "Keep looking for other survivors. Don't spend too much time on each one. If they don't surrender, kill 'em."

There was the sound of a boot crunching rubble beneath its sole coming from inside the one-time pharmacy. Emilio tensed. He was toward the back of the building, but the pharmacy wasn't large. The sound of footsteps came closer. Whoever it was, the person was pushing aside debris, opened cabinets, tossed aside bodies, and did what sounded like a thorough investigation. From outside, "Find anything? Don't waste your time, do a quick search. We still have other buildings before we move on to the next village."

"Nothing yet," said another man, also in a foreign language. They were speaking Díenstadi. These were Macabéan soldiers.

"Hurry," replied the first. "It will be noon in two hours and I would like to eat on time today."

Inside, the footsteps came closer. Looking around him, Emilio found the blade he had used to cauterize his wound. He grabbed it with a clenched fist and slowly picked himself up off the ground, using the wall behind him as a crutch. Slowly, and quietly, moving to the forward edge of the room, he took up a position just behind the opening where there once stood a door. The Macabéan soldier stepped closer. Emilio cut his breathing. From the other side of the opening poked in the muzzle of a rifle. Then stepped a black boot. It seemed an eternity as the soldier stepped into where the Havenic fugitive was hiding. Before either of them truly knew what was happening, Emilio went to stab him in the neck. But just as cold, hard steel was about to make contact with warm, soft flesh, he heard a buzzing sound above him. Looking up, he saw, for a very brief moment, a low-flying drone. And that's about all he saw, as something struck him in the head and he, once again, went out cold.

By the time he woke up, he was no longer in Ishme-Dagan.

III

Emilio awoke inside a cold cell with concrete floors and non-insulated brick walls. The fourth wall was made of bars, with a locked door on one side. How did he get there? The last thing he remembered was waking up within the ruins of Ishme-Dagan.

As he slowly regained consciousness, he realized that he was in a cell with dozens of others. In fact, it was so overcrowded that, like him, most slept on the floor. Only a lucky two were on cots. Others noticed him awake, but said nothing. They seemed destitute, lacking of energy, and hopeless. Most wore the uniforms of Havenic soldiers, although many did not. On the other side of the cell door, across the hall, was another one just like his and it too was filled to the brim with Havenic prisoners.

"What is this?" he asked, to no one in particular.

One man, behind him, replied, "El infierno, hermano."

Emilio rubbed his head, which hurt quite a bit. Where his hand touched there was a large, hard bump and as his fingers traced the pain he felt a scar. That suddenly reminded him of the wound in his gut, and he frantically lifted his shirt to inspect it. It had been infected the last he remembered. How long had it been? How bad had the infection gotten? But when he looked at it, there was no more pus and, instead, there were professional stitches. Someone had cleaned him up.

A uniformed soldier appeared outside. He struck the bars with his baton loudly, and then his narrow eyes settled on Emilio. He said, in his alien, Díenstadi tongue, "You, you are awake." Seeing that the Havenic was inspecting his wound, the soldier chuckled and added, "You can thank the empire for that, friend. If it was up to me, though, the lot of you would have been shot where we found you."

"Mi familia," said Emilio, who didn't understand a word that the guard was saying.

"Familia?" repeated the guard, who obviously did not know the language of his prisoners. "What is that? Family? Oh, you'll be seeing them soon enough. For now, it's time to eat."

He unlocked the cell door and ordered the group inside to line up outside against the bars. When Emilio stepped out he noticed the armed soldiers standing above them, on passages protected by concrete barriers. They were all pointing their rifles at the prisoners. The guard opened the other door and had those do the same thing as their predecessors. He then walked down the hall and continued doing the same thing until what seemed like more than a hundred Havenics in rags and worn uniforms were standing in a line on either side. The guard inspected them all, lightly hitting some in the stomach or in the leg with his baton, as if to prove to them that in his power was the capacity to do much worse. Above, the other soldiers with rifles grimly kept their posture, never lifting or moving their rifles, not even to scratch an itch.

They were finally moved out of the hall into another one, which they followed until turning down a different path until, finally, they reached a large mess hall. There were thousands of prisoners already seated at metal tables in the large room. Emilio and his group were led past these tables to a long line, in which they waited until they reached the back where behind a glass barrier there was a kitchen and cooks. A single bowl of god knows what was passed to each one of them through an opening in the glass, which they took to a table that the guard led them to. With all the hub-bub it was quite loud, as the guards evidently did not care if the prisoners talked among themselves. But, at first, his table was silent. Everyone was too focused on eating. Emilio couldn't even remember when the last time he had a bite of food was. How long since he had been captured? His last meal was the day before that.

Finally, with some food in his stomach, he looked up at the man across from him and asked, "Are you all prisoners of war?"

The man nodded, and replied, "Most of us. Some are just villagers that were picked up after the battle. Who were you with?"

"2189th battalion, 219th infantry division," answered Emilio.

He heard a laugh from beside him, and another man said, "You poor assholes were part of the reinforcements that were supposed to turn the tide, weren't you? The ones that counterattacked. I heard they chewed you up and spat you back out, and that those who lived should consider themselves lucky. Not that any of us faired any better. My unit retreated south early on and those bastards still managed to catch up to us. Now I'm here."

Emilio shrugged. "I don't remember much, to be honest," he said. "I was shot early in the afternoon, not long after we counterattacked. Where are we? How far from the front?"

"The front?" barked the same man, "Hah! There is no front, compadre. Our boys are in headlong flight southward. I've heard rumors of a new line, but every new prisoner who walks into these walls tells me the same thing. Our army is no longer an army, just rabble in rout. Nos jodieron bien en Ishme-Dagan. The cream of the crop, and all the new armor we imported, is gone. Dead. Destroyed. No more. The war is as good as over."

"And us? What happens to us?" asked Emilio.

The man shrugged. "¿Quién sabe?"

As it turned out, all of these prisoners, including Emilio, would be on their way home. But only after almost a years' wait. Every day for the next nine months they did the same routine, spending almost all of their day in a cell, with about 30 minutes of exercise time split up into three blocks — morning, afternoon, evening — and two meals. The latter was always the same gruel they ate that day. The food never got better. And the worst was yet to come.

When winter came the bitter winds entered through the small holes in the walls to freeze the prison's inhabitants. Many saw their toes and fingers succumb to frostbite. A great deal died from the cold and illness. But the cells were always full, because there were always new prisoners of war to replace the dead. The prisoners buried their own and, ironically, belonging to a burial crew became a respite from the misery. Those chosen were bussed to a field less than five kilometers away from the prison, which Emilio learned had been co-opted as a prisoner of war camp, where they dumped the bodies into a communal pit and covered back up with dirt. It was gruesome work, but burial crews got a third meal and it gave them almost eight hours of time outside of their cells. It was, in their world, a great privilege. Emilio did what he could to always be chosen. Typically, that meant being a "good boy" and doing what the camp guards told him, including informing against prisoners who caused trouble. When one of the prisoners tried to stab him in the showers, the Macabéans moved him to a separate barracks building that was less crowded and housed the "privileged" prisoners of war — typically, the officers and other informants who had been "done."

Not all the officers were well-off. They were, by virtue of their position in the Havenic army, the best informed of all the prisoners in Macabéan hands. Many came back from interrogation scarred from torture. Some told Emilio their stories. They were asked questions like: How many divisions around this city? What was the status of the equipment of these units? Who were their officers? All questions with answers that most officers in here would not know because the situation had changed drastically since the end of the Battle of Ishme-Dagan. The Havenic army was in disarray, its leadership in chaos, and nobody knew much except what was immediately relevant to them. The prisoners in this camp knew even less, although the worst torture was reserved for the most recent newcomers.

He was spared much of the violence, largely because of his willingness to cooperate to the extreme and the fact that he had been a mere plebeian. But he saw the beatings in the courtyard on almost a daily basis. Prisoners who made it to burial duty and tried to escape in the field were simply shot. Those desperate enough to steal food in the mess hall were beaten to nearly an inch of their lives, and many were just killed afterward by the man they had tried to steal from.

By the war's end in the summer of 2018, Emilio did not consider himself lucky to be alive. His life had come at the cost of his humanity.

IV

By the time he was given his freedom, loaded onto a bus, and driven southward, Emilio had almost forgotten about his wife and newborn son.

He looked dejectedly out the window toward the countryside. The land he had been sent to defend was now under foreign occupation, ceded to the Golden Throne by treaty. In this new post-war world, there was no room for Havenics like him in their old land. Millions of his kind were loaded on busses like this one, or else trucks or made to move on foot, and deported to south of the new border between the empire and republic. They stopped twice a day for bathroom breaks but were fed on the move. The food was no longer that soup, which Emilio had become accustomed to. They were given military rations, which were not much better. Once on the other side of the frontier, they were dropped off with only the clothes on their back — some of them were "fortunate" to get new prisoner garb but many still wore the same uniform they had been captured in — and their transports turned around, never to be seen again. Now "home," the once prisoners were expected to make it on their own. Tens of thousands stood there, at first, motionless, and clueless about what to do next. There were no Havenic authorities there to help.

How far the war had come, whether the Golden Throne's armies had fought here, Emilio did not know. But, it all looked like a warzone to him. Not all of it could have been caused by the fighting, that much was clear. The border town he had been left at, Juradeño, was in a state of anarchy he would almost immediately find out. With no traces of the Havenic army, the hundreds of thousands of released prisoners organized authority of their own. It was a totalitarian authority. The townspeople were long gone, or dead. Some of their women had been left behind and now "worked" as prostitutes. To call it work was hyperbole because they were not paid. There was no food for anyone except that controlled by the town authority, which was little more than a group of strongmen. Emilio and those who had come with him were told to move along at the point of the gun.

He, at any rate, had only one thing on his mind: returning to his wife. Before the war, they had lived in the city of Cuatro Vientos and he assumed they were still there. And so, in that direction, he walked the long journey home.

Although the richest farmland had always been in the north, the lands now occupied by the Golden Throne, he expected some sign of life and abundance here. But the fields were barren and there were no workers tilling the soil. It looked as if there would be no harvest this year. Hunger did not have to wait for the harvest, or lack thereof, however. The side of the road was inhabited by the homeless refugees produced by the war. They begged for food and water from those who didn't have any either. Women sold their bodies to those who promised them scraps, only to find out that they had been taken advantage of half of the time The corpses of those who did not make it were left strewn where they had fallen, sometimes in the middle of the road itself. Emilio, and others, lived off the weeds. The water he drank he produced overnight, using the skills he had learned in the army to collect it from the condensation, using his clothes to funnel it into a canteen he had found on a dead man's body. Somehow, he survived. But, truth be told, it hardly felt like survival. He felt dead in a dead land.

He should have hated the Macabéans. He should have hated the government that got them into this war, in the first place. Instead, he hated the people. He hated how they robbed from each other. He hated how they took advantage of each other. He hated how they gave up and died. He hated their ignorance and their plight. He hated how they could not take care of themselves, even though it wasn't all their fault. He hated that they could not pick up the pieces and had instead devolved into barbarians.

This hate would grow into much, much more when he arrived home.

It defined his new self, his ambitions, and his objectives.

It would come to define Safehaven.